When I stayed two weeks in the Translators’ House Looren in March 2023, I heard that they regularly held workshops, but I didn’t ask any details, thinking that they certainly would not be about Chinese literature anyway. And so – as I felt very much inspired by my visit – I quite straightforwardly inquired to the Looren administration if I could organize a workshop on the translation of Taiwan poetry myself. I had no idea that their workshops were usually organized with other parties (schools etc.) and include all meals for the participants, provided by the host of the Translation House – increasing the total costs. So I proposed that we cook ourselves, drew up a programme, and whereas the workshops usually involve only two languages (the source language and the target language), I proposed to translate from Chinese into several European languages. Nevertheless the administration welcomed us and so I carried on with organizing the workshop.

The participants

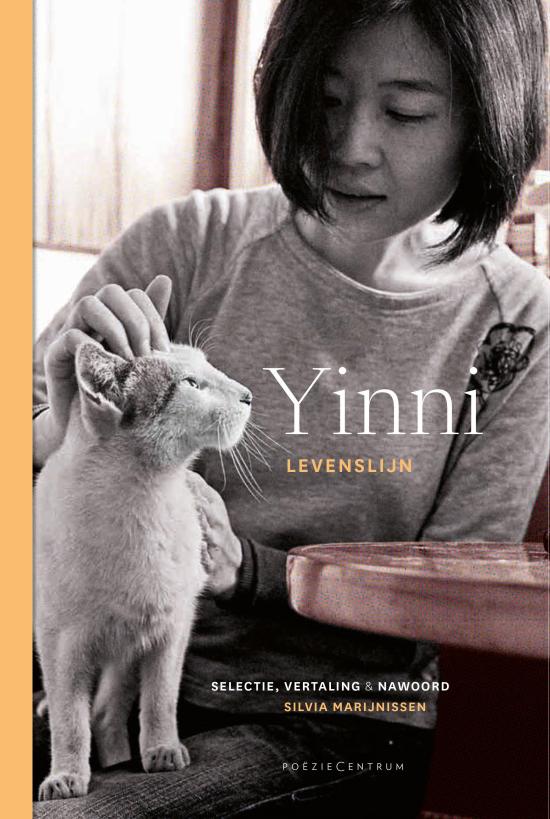

As I enjoy translating poetry I suggested to several translators in Europe that we have a practical translation workshop on the poetry by Ling Yu from Taiwan, whose work I was working on myself. Ling Yu is a renowned poet in Taiwan and had just won an important prize in 2022 for her last collection Daughters 女兒. I knew that Nic Wong (from Hong Kong) was translating this book into English, that a French edition of a selection of her poetry had just been published, and in Switzerland Alice Grünfelder was also very interested in her work. Unfortunately the French did not have time to participate, but three Italian translators, Rosa Lombardi, Silvia Schiavi and Cosima Bruno, the last based in London, joined us; as well as Dylan Wang, a native speaker of Chinese based in London, and Tony Yu, Yu-sheng Tsou and Wen-chi Li from Taiwan, the last two being based in Munich and Oxford respectively. The native speakers, I have to add, all have an excellent near native proficiency of the second language (English or German).

I had thought about inviting the poet herself for the workshop, as I personally often collaborate with the poets I translate, asking questions about the meaning of words or sentence structures that are unclear to me. Sometimes they clarify allusions. On the other hand, there are also translators who explicitly do not want to contact the poet, in order to be free to create their own interpretation. So I decided not to. Besides we had a few native speakers in the workshop, which was maybe more useful, because it emphasized how different native speakers read and interpret a text.

Reasons for joining

We all had different reasons for joining. Most participants work in universities, as PhD’s, teachers or professors of either literature, translation studies or philosophy. They all find time to translate literature or poetry every now and then, out of personal interest and for their teaching and researching topics. Some of them also write poetry themselves, some are more focussed on language, others have a philosophical background or work on literature in a more historical and social setting. I was the only independent freelance translator. What I miss most as a translator from Chinese into Dutch, after years of solitary home working, are the discussions with colleagues. There are only a few people working on Chinese language literature in the Netherlands, and we hardly meet because I live in France. The group that came to Looren turned out to be a perfect mix for the exchange of ideas.

The practical organisation

Many of us did not know each other personally. We arrived at the weekend and we got to know each other during our first get-together dinner on Sunday, kindly offered by Alice. And luckily, I must add, because somehow it had completely passed me by that shops are closed on Sundays in that vicinity! Our organization of the meals for the rest of the week, some more Italian, some more Asian, proceeded in the same way as the workshops themselves: both efficient and relaxed, and always interesting and convivial.

Our organization of the meals for the rest of the week, some more Italian, some more Asian, proceeded in the same way as the workshops themselves: both efficient and relaxed, and always interesting and convivial.

Before the workshop started I had asked all the participants to choose one or two poems of Ling Yu. We shared these Chinese poems and our first draft translations with all the others (everybody translated in their own personal language, including English, Italian, German and Dutch). So we all had a chance to prepare the poems in advance. During the week everyone presided over a half-day session, in which the difficulties of the specific poem were presented by the temporary chair. So who is Ling Yu and what is her poetry like?

A short biography of Ling Yu

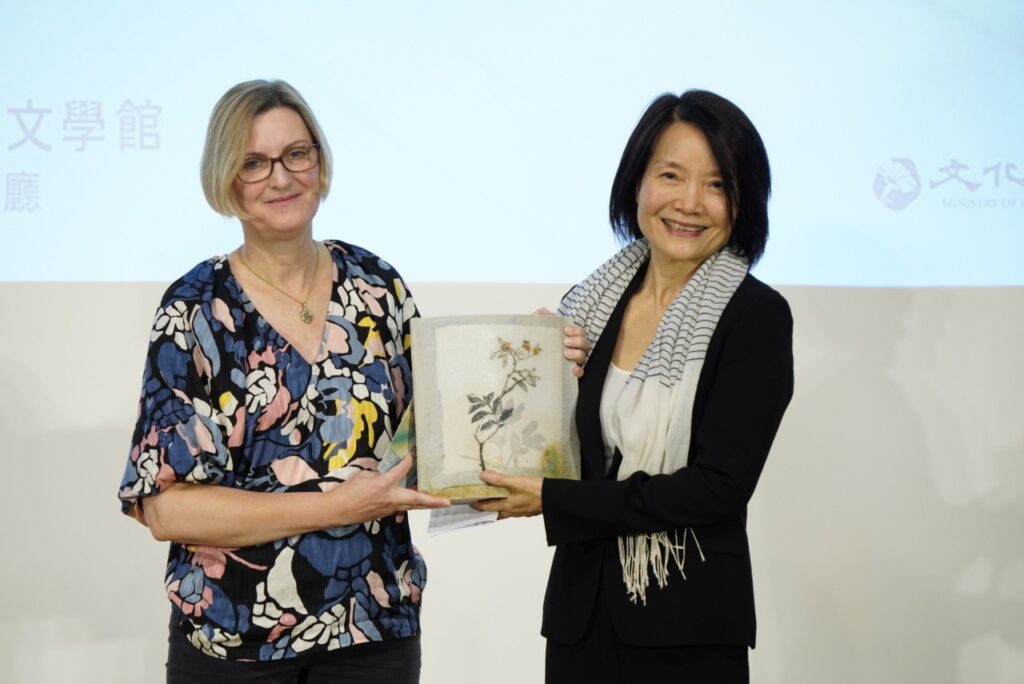

Ling Yu (Taipei, 1952) did a BA in Chinese literature at the National University of Taiwan and an MA at the Department of East Asian Languages and Literature at the University of Wisconsin. She has worked as an editor of the book supplement for the Taiwan Times (台灣時報), was a visiting professor at Harvard University in 1991-1992, and worked at Yilan National University from 1992 to her retirement in 2021. In addition, she was an editor of the poetry journal Modern Poetry (現代詩), co-founder and editor of the pioneering journal Poetry Now (現在詩, along with Hsia Yu 夏宇and others) and deputy editor-in-chief of The World of Chinese Language and Literature (國文天地雜誌社). She received several major awards in Taiwan and has been invited to various international poetry festivals.

The poetry of Ling Yu

Ling Yu’s idiosyncratic poetry is heavily inspired by history, art, philosophy and mythology. Besides Taiwanese, Chinese and Japanese culture, she also refers to Western classics. Her work can be as surprising as Li Bai, as melancholic as Du Fu, or as complex as Li Houzhou; and with Tao Yuanming her poems share a love of a simple life, without the bustling cadence of cities and politics. Her work refers to very diverse painters as well, such as the Chinese Badashanren (eighteenth century), the American Georgia O’Keeffe (twentieth century), or the Mexican Frida Kahlo. Zhuang Zi, whose work she considers a pinnacle of East Asian aesthetics, seems a big source of inspiration. In her own poetry too, Ling Yu emerges as someone who loves contradictions and paradoxes: There is light versus dark, day versus night, freedom versus captivity, the hermit versus society, rock versus water: ‘I want to dream but not sleep / I want to walk but without feet’.

As we saw during the workshop her style is calm and thoughtful, sounding elegant and natural, without obvious rhyming, metre or language games. Ling Yu registers feelings and insights in a relatively pure way, without using many adjectives and adverbs. The poems show a sensitive soul, modest and controlled, with sometimes a Zen Buddhist undertone. Her poems stand out for their original metaphors and for their serial forms. She might very well be the poet who has written the most 組詩 ‘serial poems’ in Taiwan, even in all Chinese language poetry.

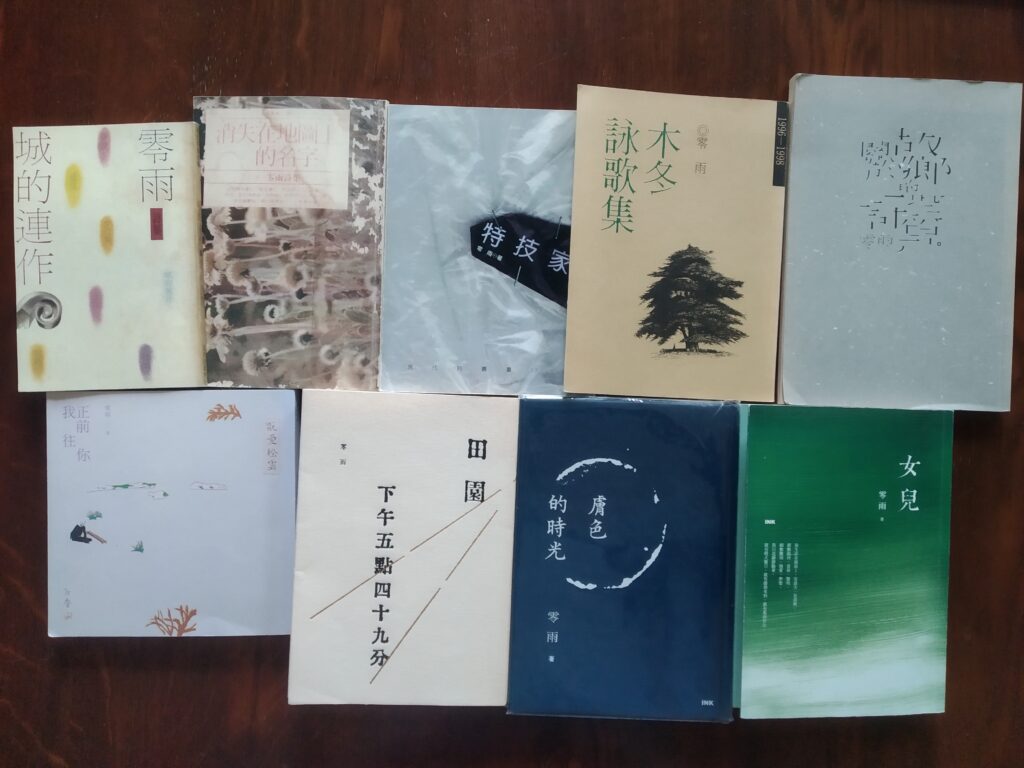

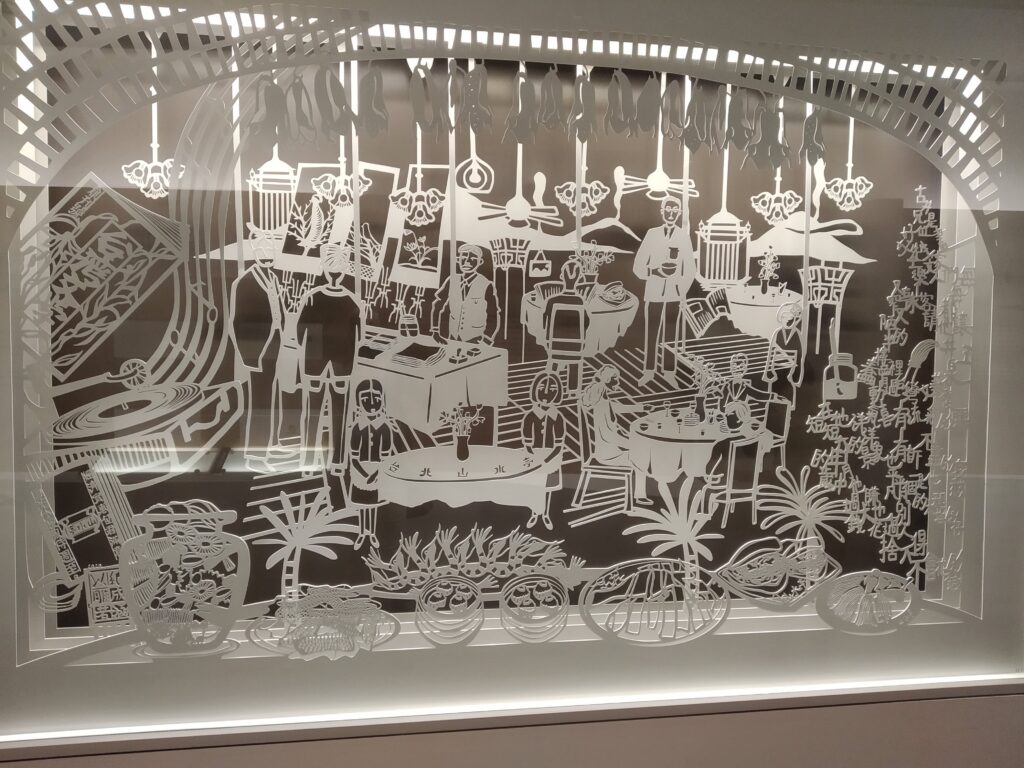

Ling Yu has published nine collections since her first in 1988. Each collection has a different focus, but female emancipation, the damage capitalism does to natural and human life, train travel, the classics, landscape and scenic elements recur often. For the workshop we mostly translated poems from her last two collections: 《膚色的時光》Skin Colour Time (2018) and 《女兒》 Daughters (2022). That first seems to dive into the Chinese tradition and the latest collection was written in response to the illness and death of her mother. Here she considers what it means to be a daughter, a mother, a woman, as an individual, in a family and in society. In addition, the collection is also a tribute to Japanese artist Ando Hiroshige (1797-1885, also known as Utagawa Hiroshige, born Andō Tokutarō), of whom she herself says that he/his work acts as a kind of mother to her; both ‘mothers’ have accompanied her throughout her life.

Ling Yu has published nine collections since her first in 1988. Each collection has a different focus, but female emancipation, the damage capitalism does to natural and human life, train travel, the classics, landscape and scenic elements recur often. For the workshop we mostly translated poems from her last two collections: 《膚色的時光》Skin Colour Time (2018) and 《女兒》 Daughters (2022). That first seems to dive into the Chinese tradition and the latest collection was written in response to the illness and death of her mother. Here she considers what it means to be a daughter, a mother, a woman, as an individual, in a family and in society. In addition, the collection is also a tribute to Japanese artist Ando Hiroshige (1797-1885, also known as Utagawa Hiroshige, born Andō Tokutarō), of whom she herself says that he/his work acts as a kind of mother to her; both ‘mothers’ have accompanied her throughout her life.

Difficulties in translating

Part of our time was spent on denominating the style, the textual references and the exact meaning, function or effect of the Chinese words, in order to find the accurate words in our respective languages. Some translation problems are not limited to Ling Yu, but are true for translating Chinese into European languages in general. Well-known examples are the choice of whether or not to use capitals (non-existent in Chinese); the lack of verb conjugations in Chinese (the perception of time is different); totally different sentence structures; the lack of singular and plural forms and of articles, as well as the lack of demonstrative and possessive pronouns where European languages require them.

Of course, the completely different use of punctuation is also an issue. We struggled for example with Ling Yu’s frequent use of the dash, which cannot be used so abundantly in European languages, we mostly agreed. Besides, we failed to see a coherence in the use of it. Like most modern poems in Chinese Ling Yu does not use punctuation at the end of a verse line, nor the full stop to mark the end of a sentence. Enjambments are quite commonly used, but many Chinese poets use them mostly to create a tension or emphasis only. Ling Yu, however, regularly has inventive enjambments, using a combination of sentence structures and ambiguous words to create ambiguity in a meaningful way. For instance in these lines from the 6th poem 岩石‘Rocks’ of the series 我的名字叫海 ‘My name is sea’ in Daughters:

啊這些年少的—— Ah, these younger (ones) –

岩石終於 rocks finally

定居下來 settle down/settled down

Here the 年少的in the first line can be read as a noun, meaning the younger ones, or as an adverb to the 岩石, rocks in the second line, meaning the young rocks. Or in these two verses from the poem 調換 ‘Exchange’ in Daughters:

她的胃已經不能裝我 Her stomach already is not able to hold me/I

給他的食物 the food given to her

This whole sentence, when read as an enjambment, can easily be translated very straightforwardly as: ‘Her stomach can no longer hold the food I gave her.’ But the meaning of the isolated first verse line, ‘Her stomach can no longer hold me’, also comes into play. This reading can be interpreted as: she is no longer able to deal with me – in other poems from the collection it is clear that the mother is bedridden and can no longer communicate (see the poem below). The translator has to be inventive to reproduce a similar ambiguity in the European language.

Sometimes the different etymology of words seemed important to a translator. The first lines of the 7th poem in the series 看畫 ‘Looking at paintings’ (based on Hiroshige’s ‘The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō’) give a good example:

被時光燒成了灰燼的富士山

像一座紅色的海市蜃樓

These lines can be translated as:

The Fuji that has been burnt to ashes by time

seem to be a red mirage

Literally the Chinese phrase for a fata morgana consists of the characters of: see – city – marine monster – storied buildings. In former times people assumed that the breath exhaled by a monstrous marine animal created the illusion of cities or buildings in the air above the sea. In the European languages the fata morgana was thought to be created by the witchcraft of the Italian fairy Morgane (from the King Arthur legends); what the visual illusions looked like is not made explicit. As the storied buildings in the Chinese seem important in the series, the translator wanted to find a way to keep them in the translation.

Yet another challenge gave the linguistically quite simple poem木頭人, which literally means ‘Wooden man/figure’ and is short for 一、二、三木頭人 ‘one, two three, wooden man’. This is the Chinese name for the child’s game that is known all over the world by different names. The English say ‘one, two, three piano’, just like the Flemish; the French say: un, deux, trois soleil; the Germans call it ‘eins, zwei, drie Ochs am Berg’; in Italian it is ‘uno, due, tre… stella’; and the Dutch have ‘Annemaria koekoek’. The popular (and horrible!) South Korean Squid Game is based upon this game, but luckily that has nothing to do with this poem. The full Chinese poem goes as follows, with a literal translation:

木頭人 wooden man/figure

一、二、三木頭人 one two, three, wooden man

我和我的小時候 I and my childhood

玩著這個遊戲 playing this game

一、二、三木頭人 one two, three, wooden man

我的母親──我和她玩 my mother – I play with her

她躺在床上 she lies in bed

我和瓦蒂一起扶她,坐起來 I and Wati together help her, sit

躺下來,翻身 lie, turn

和她說話 talking with her

她不回答 she does not reply

也不點頭搖頭 she does not nod or shake her head

還好眼睛會動,會看我 fortunately the eyes can move, can see me

一、二、三木頭人 one, two, three, wooden man

這個遊戲回來了 this game is back

我和我的小時候 I and my childhood

Obviously the wooden figure here has a richer meaning than just the game because the ill mother is like a wooden doll unable to move. In the first stanza Ling Yu again has created a meaningful enjambment in the second and third line, which can be read as: I and the game that I played in my childhood/when a was a child’, but the second line also stands by itself: ‘I and my childhood’, all the more because it is the last line of the poem as well. It also seems important because it draws attention to the fact that the serious illness of the mother throws the I back into time, back into childhood. In the third stanza the Wati瓦蒂 is interesting. Everybody familiar with Taiwan knows that there are a lot of people from Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, who come to Taiwan to work in households. Wati is the name of such a person from Balinese origin. In other poems we came across the generic term 外勞, meaning labour that comes from outside of Taiwan. It is such a short term in Chinese, clear to everybody knowing the language, but in European languages it becomes long, sometimes superfluous for the essence of the poem and it may even arouse unwelcome associations with discrimination.

Another interesting part of the whole process of the workshop was to see which poems everyone selected. It seems to me that the native speakers of Chinese had in general fewer problems in selecting poems that are strongly grounded in Chinese (or Asian) tradition, as often the titles already indicate, such as 杜甫, 767 ‘Du Fu, 767’, 夢見文言文 ‘Dreaming of classical Chinese’, or 松雪齋 –致黃公望 ‘Pine Snow Studio – to Huang Gongwang’ or the series 看畫 ‘Watching paintings’ dedicated to Hiroshige. Personally I always hesitate to select and translate poems that I fear are ‘too Chinese’ for the Dutch readers to understand because I am afraid it will scare them away or that I have to add too many footnotes to explain them. But these poems actually all turned out to be really interesting, so maybe I am just wrong with my usual way of selecting and should put more effort into making them work in translation!

Too soon our week was over and we all split up again… The breathtaking view looking out of the house, the comfort in the house, the easy-going atmosphere, the generosity of everybody present… The whole experience has led to a very productive week, in which we found a good balance between relaxing and working. Dylan Wang wrote a poem as a memento for this highly inspiring week in which he highlighted the things that we discussed. You can read it here:

At Home in Translation – Alice Grünfelder · literaturfelder

Many thanks to everybody involved, and special thanks to Tony Yu who made all the photo’s and to the incredibly supportive team of the Tranlators House Looren for accommodating us!

Waarom zou je eigenlijk poëzie lezen? Ik krijg nog al eens de opmerking dat het zo moeilijk is… Tegen pubers gekscheer ik wel eens dat gedichten gewoon de voorlopers van Instagram zijn. Wat we nu op social media doen – dingen uitwisselen om te laten weten waar we ons zoal mee bezighouden – dat doen mensen al duizenden jaren in gedichten.

Ik ken vooral de poëzie uit China en Taiwan goed, en daarin wordt er gedicht over alles: wolken, een landschap, een gebouw, een gevoel, een uitje met vrienden, een dier, een idee, gebeurtenis of herinnering… gedichten waarin recepten zijn opgenomen ken ik ook! Soms is er wat meer diepgang, soms wat minder. Soms is een gedicht wat abstracter, soms wat minder. Meestal is het zo geschreven dat het aandacht trekt. Vaak met de bedoeling de lezer over een onderwerp na te laten denken.

Dichters laten zich zelf ook wel eens uit over poëzie. Hsia Yu waardeert dat poëzie bij iedere lezing weer een ander inzicht geeft: ‘die gedichten / ik merk dat ze veranderen met het licht / als kattenogen’. Zheng Xiaoqiong vindt gedichten troostend en verslavend: ‘Rozen en poëzie / troosten mijn gewonde ik, ze zijn bedwelmender dan opium.’ Chen Yuhong schrijft: ‘poëzie is voor de toekomst’ (en liefde is voor nu). En voor Ye Mimi kan poëzie heel groot en ook heel klein zijn:

‘Poëzie kan heel groot of heel klein zijn, het kan een werkwoord zijn of gewerkwoord worden, het kan ice tea of een fles heet water zijn; elk woord of gezichtsuitdrukking, elk jengelend kind of een door de dageraad wakker geschenen meer, die kunnen allemaal best voor 77,7 procent poëzie bevatten. Met andere woorden, poëzie is niet per se geschreven, maar beweegt zich meestal door ons dagelijkse leven. Je kunt zelfs iemands bloedcirculatie heel erg poëtisch beschrijven of de kleuren van gerechten kunnen simpelweg door poëtische sappen zijn gezouten.

(Iedereen kan een dichter zijn, maar het is absoluut niet zo dat iedereen met woorden anderen kan gedichten. Natuurlijk hoeft een dichter anderen ook niet per se te gedichten, heel vaak is het door mij gedichte zelf een persoon, die met niemand iets te maken heeft.)’

Dichters vertellen ook waarom ze schrijven. Zo geeft Jidia Majia in een lang gedicht wel 55 reden waarom hij poëzie schrijft: uit begrip of onbegrip, uit haat of liefde, om een gevoel van geluk of onrecht uit te drukken, uit hoop of wanhoop. Sommige redenen zijn grappig, andere hoogdravend. Samen vormen al die redenen ook een verknipte autobiografie, maar deze reden blijft je toch het meest bij: ‘Ik schrijf gedichten omdat ik een toeval ben.’ Misschien zouden wij gedichten kunnen lezen omdat wij allemaal een toeval zijn?

Van heel wat gedichten worden tegenwoordig ook liedjes of filmgedichten gemaakt, zoals deze: een gedicht van 1950 over vrijheid door Lo Lang, dat door zijn dochter, de Taiwanese zangeres Lo Sirong, op muziek is gezet. Ye Mimi (dichteres en filmmaker) zorgde voor de beelden.