Hsia Yu: ONDERLINGE JALOEZIE

verborgen wigvorm

een en een

onophoudelijke vertakking

van kou doortrokken

opstapelen

kapseizen

verzinken in meervoud

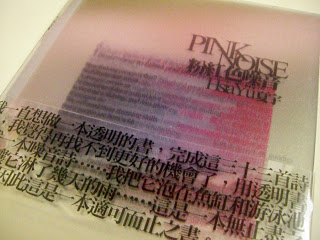

Dit is een gedicht van de Taiwanese dichteres Hsia Yu (1956-) uit haar derde bundel Wrijving: onzegbaar. Daarin hangen alle regels bijna als los zand aan elkaar; betekenis of grammaticale samenhang is duidelijk niet het eerste wat Hsia Yu hier op het oog had. De bundel is, zo legt ze in het voorwoord uit, een reïncarnatie, een palimpsest: hij bestaat geheel uit woorden, zinnen en zinsneden die ze letterlijk met een schaar uit haar tweede bundel, Buikspreken, heeft geknipt en vervolgens in een leeg fotoalbum opnieuw tot gedichten heeft gerangschikt, zoals te zien is op de foto. Ze beschouwde zichzelf ‘als een schilder’: ‘De woorden en zinnen zijn als kleuren. Op een dag zocht ik naar een woord tussen keper- en kakikleurig en ik vond “ontaarden”; die dag droeg ik een olijfgroen shirt, het “ontaarden” dat toevallig op mijn rok viel paste daar heel goed bij.’ Maar uiteraard blijkt het lastig om betekenis volledig kwijt te raken: ‘Ik moet erkennen dat betekenis een bijzonder tirannieke verleiding is. Beeldspraak is dat helemaal. En uiteindelijk verontschuldigde ik mezelf met het feit dat ik toch ook geen schilder ben, wat betekent dat ik die verleiding nu eenmaal niet kan weerstaan.’ De lezer zal hetzelfde ervaren: het is onmogelijk géén verbanden te leggen tussen al die min of meer losse zinsneden.

In Wrijving: onzegbaar speelt Hsia Yü een zinnenspel van taalbouwsels en zintuiglijkheid. Door de werkwijze is Wrijving: onzegbaar een van Hsia Yu’s meest extreme taalexperimenten, waarin ze onderzoekt wanneer taal ophoudt taal te zijn, of taal ooit ophoudt taal te zijn. De fragmentarische structuur van de ‘gevonden’ gedichten is zelfs zichtbaar gemaakt in de typografie van het boek, dat Hsia Yu zoals al haar bundels zelf vormgaf. Al met al geeft Wrijving: onzegbaar door die versnippering de lezer de meeste vrijheid, een verworvenheid van de moderne poëzie waar Hsia Yu zeer aan hecht. Maar aan die vrijheid heeft haar lezer weinig als hij niet ook over doorzettingsvermogen beschikt. En dat begint al bij het materiële boek, want voor er gelezen kan worden, moeten de bladzijden van de twee voorlaatste bundels eerst worden opengesneden. Dat Hsia Yu haar bundels uitdrukkelijk zo heeft vormgegeven, lijkt een teken aan de wand: het bevestigt dat een actieve deelname van de lezer wordt verwacht om ieder gedicht tot een uniek kunstwerk te maken, een kunstwerk dat per lezer en lezing kan verschillen.

On translating Mo Yan’s Frogs into Dutch

Some ten years ago I suggested translating Mo Yan’s Sandalwood Death (莫言,檀香刑) to a Dutch publisher. Until then the publisher had had four of Mo Yan’s books translated from the English, and I explained to them why it would be better to translate directly from Chinese into Dutch: translating is not just a simple matter of substituting words from one language to another. A translator makes decisions for every word he chooses, when you translate from an intermediary language you are in fact translating the decisions of the first translator. Besides, translating a book involves a thorough understanding of both languages, their literary traditions and the context in which the book was written. When Chinese books are translated from the English (or any other language apart from Chinese) a translator may be at work who knows nothing or very little about Chinese history, culture, society or literature.

In the end the publisher dropped Mo Yan, probably because the sales were not high enough. In 2010 I tried again with another publisher who I knew had been interested in Mo Yan for quite some time. By that time Frogs (蛙) had just come out and so I started translating Frogs. Ten days after I had finished the translation Mo Yan won the Nobel prize for literature!

In the end the publisher dropped Mo Yan, probably because the sales were not high enough. In 2010 I tried again with another publisher who I knew had been interested in Mo Yan for quite some time. By that time Frogs (蛙) had just come out and so I started translating Frogs. Ten days after I had finished the translation Mo Yan won the Nobel prize for literature!

Frogs is actually the first long novel I ever translated. I did several short stories, I am working on the famous eighteenth century novel The Dream of the Red Chamber (红楼梦together with two colleagues), and I have concentrated on translating poetry, which had become my main field of interest during my university years. I originally started translating poetry from the 1920s and 1930s in 1995, moved on to post-1950 poetry from Taiwan (on which I wrote a dissertation), and then I spent years on translating classical Chinese landscape poetry (an anthology of which was published last year as Mountains and Water/Berg en water). Translating a modern novel was different from anything I had done before.

Because all languages are different, all translation implies a transformation from the very beginning; word to word conversion does not exist. No matter which languages are involved, a translator is always creating a bridge between two worlds, narrowing a gap in space and time, trying to convey proverbs, notions, words, literary conventions, that are typical of one language into the proverbs, notions, words and literary conventions of the target language. On the one hand, the translator has to emphasize general, universal characteristics to reassure the reader with just enough familiarity to go on reading and to understand the text. And on the other hand he has to provoke the reader with strange and unusual characteristics that will enrich the reading experience. Logically, the further two cultures are separated, in space or time or both, the harder it will be to translate.

Translating a novel, I found, is not necessarily easier than translating poetry, as many people are inclined to think; it all depends on what kind of prose or poetry text you are translating. Does the prose text employ a lot of word games? Is the poem fairly straightforward? One always wants to get all the characteristics of the text across, which surface through things as sound, rhythm, style, atmosphere, mood – immaterial things that are different in all languages. A translator is one of the most thorough readers of the text, he first needs to grasp the essential elements, which he then transposes into the new language. In this, translating a good novel is essentially the same as translating a good poem. Yet, while translating a voluminous novel like Mo Yan’s Frogs one has to keep a comprehensive view of all those hundreds of pages, whereas the strength of a poem usually lies in its compactness. What I found the most difficult to translate, more than anything else, are poems with fixed forms, such as classical Chinese poetry. Because if you decide to render something of that fixed form in the translation as well, you are really limited – you have much less space than with any other literary form. And in the case of traditional poetry, the classical language, wenyan, forms an additional problem, since the language itself is very compact; in comparison Dutch is much more prose-like. Besides, classical Chinese literature is not only geographically far away from us, but centuries lie between the time of writing and the contemporary Dutch reader.

I have always been able to translate texts that I have chosen myself, texts that I appreciate personally. I like writers who enjoy in one way or other to experiment and to surprise the reader. I like writers who have a good sense of humor and exaggeration, and who are visually strong as well. Xia Yu (夏宇), for example, one of my favorite poets from Taiwan, writes in “To give time to time” (給時間以時間) that somebody is shot, and that the blood oozes out like toothpaste – which I find very funny and surprising because she more or less equals the shooting to something as common as brushing one’s teeth. The scene comes alive in your mind:

I have always been able to translate texts that I have chosen myself, texts that I appreciate personally. I like writers who enjoy in one way or other to experiment and to surprise the reader. I like writers who have a good sense of humor and exaggeration, and who are visually strong as well. Xia Yu (夏宇), for example, one of my favorite poets from Taiwan, writes in “To give time to time” (給時間以時間) that somebody is shot, and that the blood oozes out like toothpaste – which I find very funny and surprising because she more or less equals the shooting to something as common as brushing one’s teeth. The scene comes alive in your mind:

Give Time to Time

– For Yan McWilliams

Since time became time

We have had to give time to time

Being is also being this way is not so difficult either

For being to be understood as being

Later if motivation’s turn comes up let me

Grab him by the throat and put a bullet through him

This sobriety of mine

Is almost wind

In a pump organ

And mornings like this I’ll give the name of soft

And exact

Exactness of mint in toothpaste

When I drill him through his blood will ooze like toothpaste

Bringing closure to his fury and exhaustion

For once at least he’ll again be a virgin boy

In the face of death

If I claim to be a murderer

Everyone is sure to want a narrative account:

I made the day my night immense and broken**

To make this moment flecked with starlight

And moreover to have loved If death is not wanderlust

Music rises vertically

We lie horizontally

(translation by Steve Bradbury, in Fusion Kitsch)

While classical poems tend to evoke a static image like a painting, modern poems like this one are more dynamic, providing more fluid visual images, as in a film. Xia Yu’s language underlines that aspect, it is mostly prose-like language highlighted especially by striking imagery, by juxtaposing contrasting images. From a syntactical point of view, most of the sentences are more or less regular, but they are complicated by the arrangement of the verse lines which she regularly uses to create ambiguity. Her sentences interlock with one another, making it impossible to tell where one sentence ends and another begins. Thus, a new line often puts the previous one in a different light, changing its meaning, as with these lines from ‘Written for others’ (寫給別人):

I love you I love you slowing

the pace till the very slowest so slow till

we hear gear-turning

sounds slippingly on our bodies

a beam of light that is the movie picture

only invented by someone to darken

the room to teach us

to make love slowly in the slowest motion

To transpose such language games into a different language can sometimes be quite difficult. But with patience I usually find a solution in the end, by devising a game that works equally well in Dutch.

The prose poetry of Shang Qin (商禽), also a favorite of mine, is another good example of the prose-like style of modern Chinese poetry. Shang Qin’s poetry is very human and compassionate, but without becoming sentimental, because he combines the tragic and the comic in such a striking way. With his long, winding sentences he slows down the process of reading. A few sentences depict an imaginative scene, giving the reader food for thought. In ‘Giraffe’ (长颈鹿) for example, he draws attention to the notion of ‘time’ and ‘imprisonment’:

The prose poetry of Shang Qin (商禽), also a favorite of mine, is another good example of the prose-like style of modern Chinese poetry. Shang Qin’s poetry is very human and compassionate, but without becoming sentimental, because he combines the tragic and the comic in such a striking way. With his long, winding sentences he slows down the process of reading. A few sentences depict an imaginative scene, giving the reader food for thought. In ‘Giraffe’ (长颈鹿) for example, he draws attention to the notion of ‘time’ and ‘imprisonment’:

After the young prison guard noticed that at the monthly physical check-up all the height increases of the prisoners took place in the neck, he reported to the warden: ‘Sir, the windows are too high!’But the reply he received was: ‘No, they look up at Time.’

The kindhearted young guard didn’t know what Time looks like, nor its origin and whereabouts, so night after night he patrolled the zoo hesitantly and waited outside the giraffe pen.

(translation by Michelle Yeh)

In Mo Yan’s writings, too, I appreciate the sense of humor and the grotesque. One of the opening scenes at the beginning of the Sandalwood Death, where Meiniang dreams about her father being beheaded, becomes comical when the chopped head goes on the run and defends itself with its plait against the wild dogs that follow behind. Such surprises, which set the tone for the book, are are a lot of fun to translate, because you often need to accentuate things to make sure that the humor comes across.

In his use of language Mo Yan is very different from poets like Hsia Yu and Shang Ch’in. Both poets try to push the Chinese language to its limits, creating ambiguity or slowing down reading. Mo Yan is above all a story teller in the oral tradition – in all his novels, technically and structurally diverse as they may be. He writes in colloquial language, using a lot of repetition, exaggeration and irony, inserting many four-character proverbs in his stories and making references to famous classical Chinese texts. His forte lies in the telling itself, and he narrates in a very detailed, baroque way, using all the senses. In Mo Yan’s writings one smells, tastes, hears, sees and feels. In-depth psychological analysis of the characters – as we find in western novels, with Flaubert’s ‘Madame Bovary’ whose inner life is described in detail as one of the best-known examples – is absent. Instead, it is up to the reader to derive from events and actions what kind of people these characters are.

It is these aspects that I have tried to bring across in the Dutch translation of Frogs. Yet, to guarantee more or less faithful effects in Dutch one still needs to adapt the style somewhat. Word repetition, for example, is much less accepted in Dutch than it is in Chinese; in fact, grammatically speaking, Chinese already involves far more word repetition, whereas Dutch language rules forces you to avoid it. For this reason, I have reduced repetition on the level of isolated words to proportions that are acceptable to Dutch readers, while retaining the oral, repetitive character of the original.

Similar considerations and choices are to be made for all text characteristics; the translator constantly needs to reflect about how certain things ‘function’ in the original text and how a similar effect can be achieved in the translation. How do you render the typical Chinese four-character proverbs or other sayings that occur so often? One could use Dutch equivalents (if not too specific Dutch), give literal translations, or paraphrase the meaning and ‘forget’ that it was originally a proverb. Again one needs to consider that colloquial Dutch makes far less use of proverbs than Chinese. Exaggerations and irony, often somewhat culturally defined, regularly need to be accentuated – if you do not the humor is lost on the Dutch reader.

Names will sometimes lead to translation problems as well. Frogs is for the greater part a long letter written by the narrator, Tadpole, to a Japanese author friend. The sentence with which he starts the long story about his aunt is: ‘Sir, it used to be good practice in our region to give children at their birth names of body parts or organs, such as Nose Chen, Eye Zhao, Large Intestine Wu or Shoulder Sun. I have not examined how this use has come into existence, probably it was rooted in the belief ‘those who have a humble name will live long’, or maybe it had something to do with the psychological tendency of mothers to consider the child as a piece of their own flesh. Nowadays this custom is not very popular anymore, young parents no longer want to give their children such strange names. Nearly all the children in our region now also have names as elegant and original as the characters in the television series from Taiwan, Hong Kong or even Japan or Korea. Most children who once were given the name of a body part or organ have changed it into an elegant one, even though there are some who have failed to do so, Ear Chen and Eyebrow Chen for example.’

It is no problem at all to translate this passage, but the choices will be crucial to the remainder of the translation. Because of the absurdity of the names, which is accentuated by the narrator’s additional information, I was forced to translate them, which is uncommon in Dutch translations of Chinese literature. Several decades ago translators occasionally translated names, since they have meanings after all, but this had an unintended ridiculous effect and sometimes irritated the reader. In Frogs the ‘body part’ names are hilarious, as the narrator (called Foot Wan or Runner himself) explains.

The narrator’s first wife is one of the few of his contemporaries who is not named after a body part. Her name is Renmei (meaning righteous and beautiful), which I have just written down in the pinyin transcription, without translating. But then her family name lead to quite a comical problem, for ‘wang’ means ‘cheek’ in Dutch; with the name Wang Renmei she seemed to have a been named after a body part after all! For that reason the family name Wang is banished from the Dutch translation…

The central character in Frogs is a gynaecologist, who works in the countryside of Gaomi, in Shandong. This woman, called Aunt, who is professionally educated, first and foremost, to help women in their pregnancies and deliveries, needs to face after a while the reality of the one-child-policy. Aunt, a loyal party member, faithfully follows the rules, and thinks of ways to implement them. More and more often, she needs to sterilize men who already have a child and to abort women who become pregnant against the rules. In the beginning of her career Aunt is celebrated as a hero, after saving the life of several women and babies who would not have made it with the old methods of the traditional midwives; but she ends up being considered the devil of the village. Through her actions, Aunt, who has been through some hardship herself, comes across as a tough person, with a personal sense of justice. She is a complex figure, a woman who remains childless herself, who holds the destiny of many babies in her hands, and who at the end of her life has an enormous guilt complex.

Many of Mo Yan’s books are set in twentieth century China and show the turbulent changes that took place in that century. Nearly all of them show social engagement, but that does not mean Mo Yan is a politically engaged writer. He is obviously not a political activist, nor is Frogs a political book. Through the ups and downs of the gynaecologist, her relatives and fellow-villagers, we read about China’s recent history, about hungry children eating charcoal during the Great Famine, and about the cruelties of the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. But the national history remains in the background, what counts is how the stories depicts the characters and their actions. These are not flat, cardboard figures, but people who have good and bad sides, they show their dilemmas.

For some of the main characters a single event or move turns out to determine the rest of their lives. In that sense Frogs appears to be a novel in the line of the French author Jean Paul Sartre, a novel about the personal responsibility of human beings for their lives and actions. For a very good reason the narrator of the book, who has taken the penname Tadpole, expresses, in the beginning, his admiration for Sartre’s plays, such as Flies and Dirty Hands, and his desire to represent the story of his aunt in such play – which he does in the final part. Mo Yan’s book mostly raises questions, without giving answers. Could his aunt have said ‘no’ to the tasks the authorities imposed on her? Why does the narrator himself not oppose to his wife’s forced abortion? Why does he feel that his career is more important than his wife and child? Why did his wife risk her life by getting pregnant illegally? In the end Frogs is about guilt and responsibility – themes that amply surpass the Chinese context.

That is my personal view of Frogs, which I developed through spending about one and a half year on translating the book. It feels as if the book has become part of me, and after its publication I checked the newspapers every week, hoping for a positive review! The reactions were somewhat mixed, most Flemish newspapers were very enthusiastic, but a few Dutch newspapers were rather neutral, showing neither much enthusiasm nor much criticism. Most readers however seem to appreciate the book and it is selling rather well. This and the Nobel prize ensure that the Dutch public will have the opportunity to read more of Mo Yan in the near future – unfortunately not all translated by me… However, I now do have two years ahead of me in which I will finally be translating the Sandalwood Death, the novel with which it all started for me.

That is my personal view of Frogs, which I developed through spending about one and a half year on translating the book. It feels as if the book has become part of me, and after its publication I checked the newspapers every week, hoping for a positive review! The reactions were somewhat mixed, most Flemish newspapers were very enthusiastic, but a few Dutch newspapers were rather neutral, showing neither much enthusiasm nor much criticism. Most readers however seem to appreciate the book and it is selling rather well. This and the Nobel prize ensure that the Dutch public will have the opportunity to read more of Mo Yan in the near future – unfortunately not all translated by me… However, I now do have two years ahead of me in which I will finally be translating the Sandalwood Death, the novel with which it all started for me.

Hsia Yu

Bij uitgeverij Voetnoot verscheen onlangs de bundel Als kattenogen met mijn vertalingen van Hsia Yu. Hieronder volgt een kleine selectie uit de bundel.

Hsia Yu (ook wel getranscribeerd als Xia Yu, 1956) mag haar lezer graag verrassen. Ze vraagt: ‘wil je niet samen met mij bij de communisten gaan?’ Ze laat bloed als tandpasta naar buiten spuiten, contrasteert de betrouwbare maandelijkse regelmaat van de vrouw met de haar toegedichte onbetrouwbaarheid, steekt de draak met dichterlijke authenticiteit, die helaas niet per se tot goede gedichten leidt, en antwoordt op de vraag ‘wie ben je’: ‘ik weet alleen dat er een draadje aan mijn trui hangt’. Hsia Yu doorspekt haar werk met eigenzinnige beeldspraak en onverwachte wendingen, die een speelsheid brengen in haar vijf bundels: Memoranda (1984), Buikspreken (1991), Wrijving: onbeschrijfbaar (1995) en Salsa (1999) en Pink Noise (2007). Hieronder een kleine selectie uit Salsa.

VOORWERPEN VANZELF LATEN BEWEGEN

iedere keer denken dat deze keer niet telt

iedere keer denken dat nu niet echt is

een scheurend geluid van zijde in de lucht

zo hard mogelijk naar binnen rennen

en schuilen

door een kiertje gluren

met een klein stemmetje zeggen: ‘volgende keer, oké?’

wanneer alles aan het gebeuren is en tot het bewustzijn doordringt

verwijdert dat bewustzijn het gebeuren

uit het gebeuren

maar om een dag later te kunnen zeggen:

‘eigenlijk’

of:

‘ooit’

iedere keer plechtig denken:

‘de volgende keer telt beslist meer dan deze keer’

waarmee de volgende keer van de volgende keer

wordt gedefinieerd

of het plan opvatten om bij de volgende spurt naar buiten

te roepen:

‘telt niet.’

voorwerpen vanzelf willen laten bewegen

uit ongeduld

wat dan inderdaad ook gebeurt

ziet iedereen vervolgens

een stoel vanzelf aankomen

‘telt nog steeds niet’

zwakjes zeggen

‘zelfs deze telt niet telt niet’

ONBEMANDE PIANO

– voor j.w.

weg

maar nog altijd strelende handen

een pianola

niemand speelt

een strand tussen de sterren

na lang staren in nevelen gehuld

omhelzingen maar hoe

gladde lichamen die als

twee omhelzende dolfijnen die als

twee ijsbergen

samen een vuurzee in gleden

hoe was het gesprek begonnen

plotseling leken al die volkomen

willekeurige steden zo precies

perfect antipodisch

aan de gepasseerde

praten om ineens te voelen dat omhelzen toch beter is

omhelzen om samen de trap af te kunnen lopen

slenteren langs een bioscoop een kaartje kopen

en een film zien om te voelen dat omhelzen machtiger is

zodat tussen al die gelijkwaardige

telkens weer aanvaarde momenten

er eentje duidelijk afsteekt

tegen de andere

BEWOGEN WORDEN

ze zegt /m/

alleen als je heel erg lang niks zegt

kun je dat

zo’n ontzettend lage /m/

ze zegt /m/

en dan beweegt ze niet

wil niet bewegen

die klank brengt geen rimpeling teweeg

in het grijsgroene meer

waarin algen

ze zegt /m/

en dan zegt ze /n/

maar beweegt gewoon niet

iemand roept haar

als een druppel op was

ligt ze in was

een meer afgesloten door was

de bodem licht deinend

maar geen lillende

drilpudding

haar bewogen worden

is in de speaker

bevroren /z/

als iemand haar flink bewasemt

op haar borst of achter haar oor

zal ze ontdooien

vallen

als een dennenappel

horen wij /d/

de in beweging geblazen donshaartjes

trekken eerst een beetje samen

worden dan warm

zetten uit

en buigen

een verlangen om te worden geopend

doordrongen

het bewogen worden

is eindeloos compact en

in te dikken

haast zonder adem

zegt ze /sj/

zonder zich om te draaien

of rond te kijken

wil vallen

almaar verder vallen

IN DE RIJ OM AF TE REKENEN

’t zij zo / ’t is nu eenmaal zo / eenzijdig / opgezegd / ’t zij zo / te laat om er achteraan te gaan / en dan nog zou er niemand te bekennen zijn / het had niet zo moeten zijn / er is vast een beter einde / in een stad als deze / ontmoet je elke dag mensen / vandaag ga ik de hele dag de verkeerde kant op / vergis me in de tijd / de hele dag gaat alles fout / hij rekent als eerste af / zou hij bij de uitgang op me wachten? / klote zeg dit bestaan / of je komt te laat / of je loopt iets mis / klote zeg dit hele leven / het angstaanjagendste is wel dat als je er achteraan gaat er helemaal niemand blijkt te zijn / je snapt helemaal niet dat je hier in deze stomme toestand zit / dat verklaart waarom je niet kunt opstaan / dat verklaart waarom je niet kunt slapen / dat verklaart bepaalde slordigheden in de retorica / geen / wonder / dat / we / allemaal / domweg / langzaamaan / oud / worden / natuurlijk draagt dat bij tot de geestelijke verlichting / ’t helpt opgroeien / maar we lijken allemaal nog onvoldoende opgewonden / onvoldoende onderscheid te maken tussen de tegenstander en onszelf / wat heeft dat voor zin als je je in een voetbalwedstrijd bevindt? / allemaal staan we samen in de rij voor een kaartje en creëren zo een aaneenschakeling / iemand wil voordringen / die moet zeggen sorry mag ik even / in de rij gaan staan om af te rekenen om daar op terug te komen / als iemand weggaat na te hebben betaald / is de volgende in de rij misschien wel verliefd op hem geworden / heel onverwachts / stil blijven staan betekent achteruitgaan je kent het wel / op dat moment ga je niet vooruit / op dat moment ga je niet achter hem aan / wat fijn zou het zijn als we allemaal samen van ouderdom in de rij sterven / als we het hebben over wij allemaal / moeten we aannemen dat we van dingen als groepsreizen houden / hoewel ik / liever alleen met hem ga / de dingen die hij in zijn boodschappenwagentje heeft geladen / stemmen met die in het mijne overeen / dat duidt toch op een mogelijkheid van gezamelijk leven niet dan? / is dat niet mooi? / in verschillende appartementen eten wij hetzelfde ontdooide voedsel / duidt dat niet op bepaalde essentiële persoonlijke voorkeuren? / is dat niet mooi? wij gebruiken dezelfde zeep en eenzelfde zeepbakje / is dat niet mooi? we kunnen onze appartementen verenigen / onze lichamen samenvoegen / waardoor sommige statistieken stijgen / en waardoor andere statistieken dalen / waardoor sommige politieke standpunten worden versterkt / en waardoor andere niet / is dat niet mooi? wij reizen samen / winkelen samen / en hebben maar één stel handen nodig voor het wagentje / is dat niet mooi? waarom houdt hij niet van mij? / precies daar bij de uitgang van de supermarkt / snapt hij niet dat hij het lot van iemand kan veranderen / hij snapt zelfs niet dat hij gelijk ook dat van hemzelf kan veranderen / de grootste overeenstemming van iets met iets anders / om iets te laten gebeuren / het maakt in eerste instantie niet uit wat / maar als hij heeft afgerekend is hij nergens meer te bekennen / en blijf ik staan waar ik sta / door hem moet de wereld weer in twee helften splitsen / die ene best tedere / die best gekwetste / die best vastbesloten / helft / die best verlossing kan krijgen / en die zelf denkt tot meer liefde in staat te zijn / die zonder twijfel / die echt bij mij hoort / ik de andere helft

HAAR EEN FRUITMAND BRENGEN

vandaag was ik ergens waar iemand me zei dat ik voortaan niet meer hoefde te komen / ik zei dat ik er toch ook al niet graag kwam / dat sommigen er wel komen daar heb ik niks mee te maken / ik ging terug naar mijn huurflat en stoomde een vis / een vriend kwam langs en samen aten we de vis / toen we hem op hadden zei hij dat hij sinds kort niet zo lekker in zijn vel zat / zijn werk kwijt / verder de trein naar het zuiden gemist om werk te zoeken / al dat werk kost je moeite en energie en vergalt je hele leven zei hij / dan koop je natuurlijk een huis met een hypotheek en een auto en dan zoek je een vrouw / je krijgt een paar kinderen je vindt het gênant als de kinderen te veel op je lijken als ze niet lijken vind je het ook gênant / we spraken wat over het verschil tussen huisbaas zijn en huurder / en toen deden we het / hij vroeg hoeveel minnaars heb je en ben ik anders / ik zei wat een onzin natuurlijk ben je anders / hij bleef doorvragen hoe anders / ik zei je bent gewoon anders en als je per se wilt weten hoe anders dan zeg ik gewoon oké je bent net zoals zij / dat zie je meteen als je naar me kijkt zei hij / je verwacht hoe dan ook het slechtste zei ik / ja daar word ik rustig van zei hij / we keken samen naar de video van de kleine zeemeermin / hij huilde toen de kleine zeemeermin haar stem kwijtraakte / we bleven onze favoriete passages terugspoelen / aten toen nog een ge¬stoomde vis / ik legde tarotkaarten om te kijken of hij werk zou vinden en hoe het met ons zou gaan / je vindt geen werk zei ik / o nee zei hij / nee je hoeft het niet eens te proberen / wat moet ik dan / je moet niks daar word je rustig van zei ik / gaan we dan trouwen vroeg hij / ook niet zei ik / er klopt niks van die kaarten zei hij hoe weet ik trouwens dat ze de waarheid spreken / dat weet je niet zei ik daar kan ik ook niks aan veranderen / waarom geloof jij ze dan / in die ene seconde dat ik de kaarten leg zei ik berekenen alle causale verbanden sinds het ontstaan van de wereld in het geheim vanzelf de juiste kaart / weg met die hele kosmos zei hij / als de hele kosmos er niet was zouden we hier nu geen kaarten kunnen leggen zei ik / ik had er geen zin meer in en zei ik wil verhuizen / nou leg dan een kaart om te kijken of je een huis kunt vinden zei hij / ik legde een kaart / de kaart zei dat ik een huis zou vinden / vraag dan nog eens of ik er met je kan wonen zei hij / de kaart zei van niet / we deden het nog een keer / we wisten toch niet wat we anders moesten doen / daarna ging hij weg / ik heb hem niet meer gezien sindsdien / misschien gaat het nog anders aflopen maar dat weet ik nu nog niet / een vriendin belde op en zei o ik weet echt niet of hij nou wel of niet van me houdt / hij houdt van je zei ik / hoe weet je dat zei ze / omdat hij niet van mij houdt zei ik / ze hing op / ik legde de kaarten weer / ik wist dat ze zo nog een keer zou bellen om te vragen en hou jij dan van hem / inderdaad belde ze / ik zei ja omdat ik zin had om haar te pesten / ik wist dat ze meteen naar hem zou bellen om te vragen zij houdt van jou waarom jij niet van haar / ze verwachtte dat hij zou zeggen ik hou van haar / ook zij verwacht het slechtste / en wordt daar rustig van / want hoe dan ook houdt niemand van haar / ze had er schoon genoeg van / wij ook / en toen ben ik verhuisd / ik heb haar geen fruitmand gebracht

Waarom zou je eigenlijk poëzie lezen? Ik krijg nog al eens de opmerking dat het zo moeilijk is… Tegen pubers gekscheer ik wel eens dat gedichten gewoon de voorlopers van Instagram zijn. Wat we nu op social media doen – dingen uitwisselen om te laten weten waar we ons zoal mee bezighouden – dat doen mensen al duizenden jaren in gedichten.

Ik ken vooral de poëzie uit China en Taiwan goed, en daarin wordt er gedicht over alles: wolken, een landschap, een gebouw, een gevoel, een uitje met vrienden, een dier, een idee, gebeurtenis of herinnering… gedichten waarin recepten zijn opgenomen ken ik ook! Soms is er wat meer diepgang, soms wat minder. Soms is een gedicht wat abstracter, soms wat minder. Meestal is het zo geschreven dat het aandacht trekt. Vaak met de bedoeling de lezer over een onderwerp na te laten denken.

Dichters laten zich zelf ook wel eens uit over poëzie. Hsia Yu waardeert dat poëzie bij iedere lezing weer een ander inzicht geeft: ‘die gedichten / ik merk dat ze veranderen met het licht / als kattenogen’. Zheng Xiaoqiong vindt gedichten troostend en verslavend: ‘Rozen en poëzie / troosten mijn gewonde ik, ze zijn bedwelmender dan opium.’ Chen Yuhong schrijft: ‘poëzie is voor de toekomst’ (en liefde is voor nu). En voor Ye Mimi kan poëzie heel groot en ook heel klein zijn:

‘Poëzie kan heel groot of heel klein zijn, het kan een werkwoord zijn of gewerkwoord worden, het kan ice tea of een fles heet water zijn; elk woord of gezichtsuitdrukking, elk jengelend kind of een door de dageraad wakker geschenen meer, die kunnen allemaal best voor 77,7 procent poëzie bevatten. Met andere woorden, poëzie is niet per se geschreven, maar beweegt zich meestal door ons dagelijkse leven. Je kunt zelfs iemands bloedcirculatie heel erg poëtisch beschrijven of de kleuren van gerechten kunnen simpelweg door poëtische sappen zijn gezouten.

(Iedereen kan een dichter zijn, maar het is absoluut niet zo dat iedereen met woorden anderen kan gedichten. Natuurlijk hoeft een dichter anderen ook niet per se te gedichten, heel vaak is het door mij gedichte zelf een persoon, die met niemand iets te maken heeft.)’

Dichters vertellen ook waarom ze schrijven. Zo geeft Jidia Majia in een lang gedicht wel 55 reden waarom hij poëzie schrijft: uit begrip of onbegrip, uit haat of liefde, om een gevoel van geluk of onrecht uit te drukken, uit hoop of wanhoop. Sommige redenen zijn grappig, andere hoogdravend. Samen vormen al die redenen ook een verknipte autobiografie, maar deze reden blijft je toch het meest bij: ‘Ik schrijf gedichten omdat ik een toeval ben.’ Misschien zouden wij gedichten kunnen lezen omdat wij allemaal een toeval zijn?

Van heel wat gedichten worden tegenwoordig ook liedjes of filmgedichten gemaakt, zoals deze: een gedicht van 1950 over vrijheid door Lo Lang, dat door zijn dochter, de Taiwanese zangeres Lo Sirong, op muziek is gezet. Ye Mimi (dichteres en filmmaker) zorgde voor de beelden.